Hands-on activities for tabletop game design workshops

The four design principles and hands-on activities I used when teaching a recent tabletop game design workshop at the Gettysburg Library. Details and resources to help others run design classes.

Last week I had the opportunity to teach an introduction to tabletop game design class at the Gettysburg Library in Adams County.

While I’ve taught free library classes before, this was a new format. Rather than the four-session one-page TTRPG class or the one-hour Dickinson College crash course, this one was a single, two-hour class.

Two hours is enough time to do more hands-on activities than the crash course, but not enough to go extremely in-depth like the four-session class.

Here’s how I structured the class in case you ever want to run a similar one.

My plan was to use the high-level structure of the Dickinson crash course, but expand (where possible) to include more hands-on activities. It was admittedly a lot of information to cover in a short period, but I tend to prefer fast moving classes than slow and detailed ones — new topic every 15-20 minutes and something to try for each topic.

The core framework was the four design principles I feel are most important:

Know who your game is for.

Choose a theme and zoom in.

Design for meaningful choices.

Think about your game in three acts.

These are based on the Skeleton Code Machine articles on kinds of fun, player types, layers of theme, player agency, and game arcs.

I discussed how I taught each of these four concepts in the Dickinson College crash course write-up from November 2025. If you want to learn more about the topics, check out that post.

What I’d like to cover here are the activities that I added to this newer class.

Principle 1. Know who your game is for.

After briefly mentioning it in the article on pitching your game at Unpub, I added a section on knowing who your game is for to the last library class I taught. It combined learning the 8 Kinds of Fun together with various models for player types, such as Bartle’s Taxonomy and the Quantic Gamer Motivations. The goal is to give participants an improved vocabulary to use when describing both games and players.

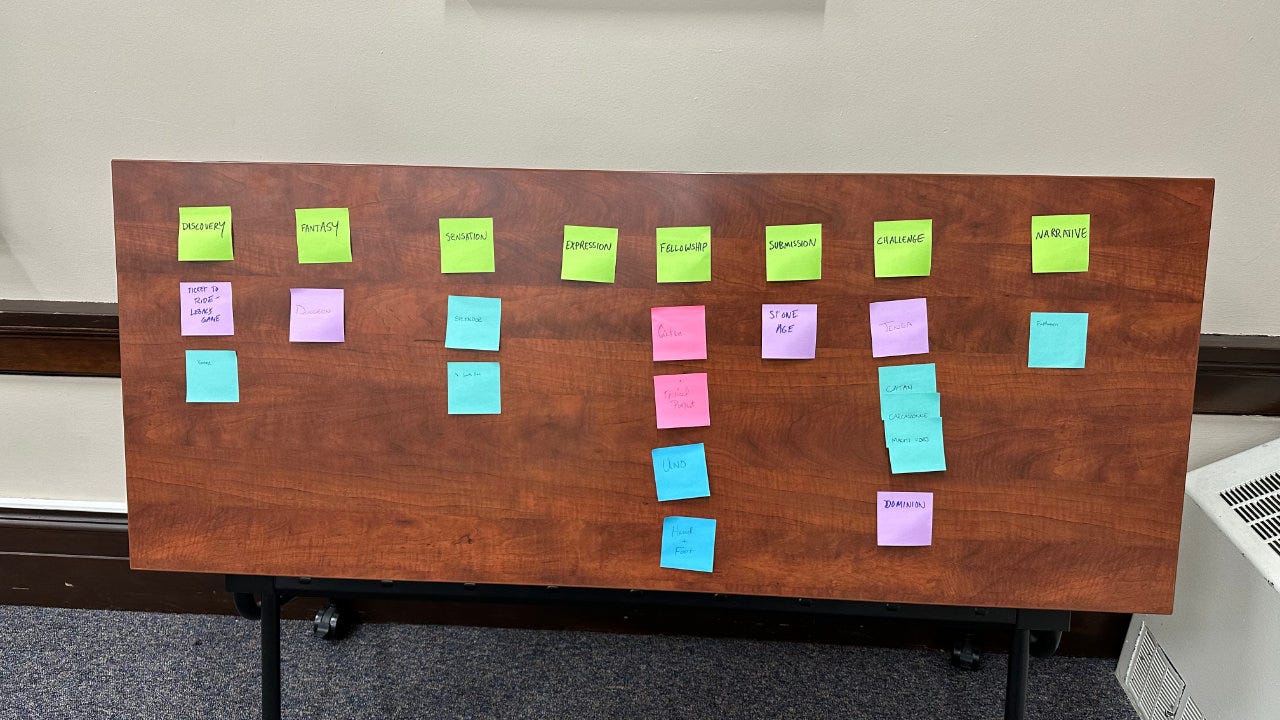

To practice, the first exercise was an easy one. I simply put the 8 Kinds of Fun on a board to form columns.1 Participants then spent a few minutes thinking of a game or two that they really enjoy — board game, TTRPG, video game, doesn’t matter. They wrote the game name on a Post-It note and stuck it under the column that they felt best reflected the kind of fun they experience when playing it.

Every time I’ve done this exercise, a few important things show up:

The same game is placed under different kinds of fun, illustrating that this is both complicated and subjective. Catan showed up under both Fellowship and Challenge this time.

Although I have a pretty good knowledge of games, there are always new ones that I’ve never heard of. It gives people a chance to share a little bit about games they love and for others to learn about games they might enjoy.

It acts like a visual bar graph of the type of games the class enjoys. You’ll notice that Fellowship and Challenge are the leaders in the photo above, with less in Fantasy and Expression.2

This exercise intentionally blurs the line between board games and TTRPGs. Both types of games are included and both can exhibit the same types of fun. This allows participants to focus on breaking games down into their parts rather than on broad categories.

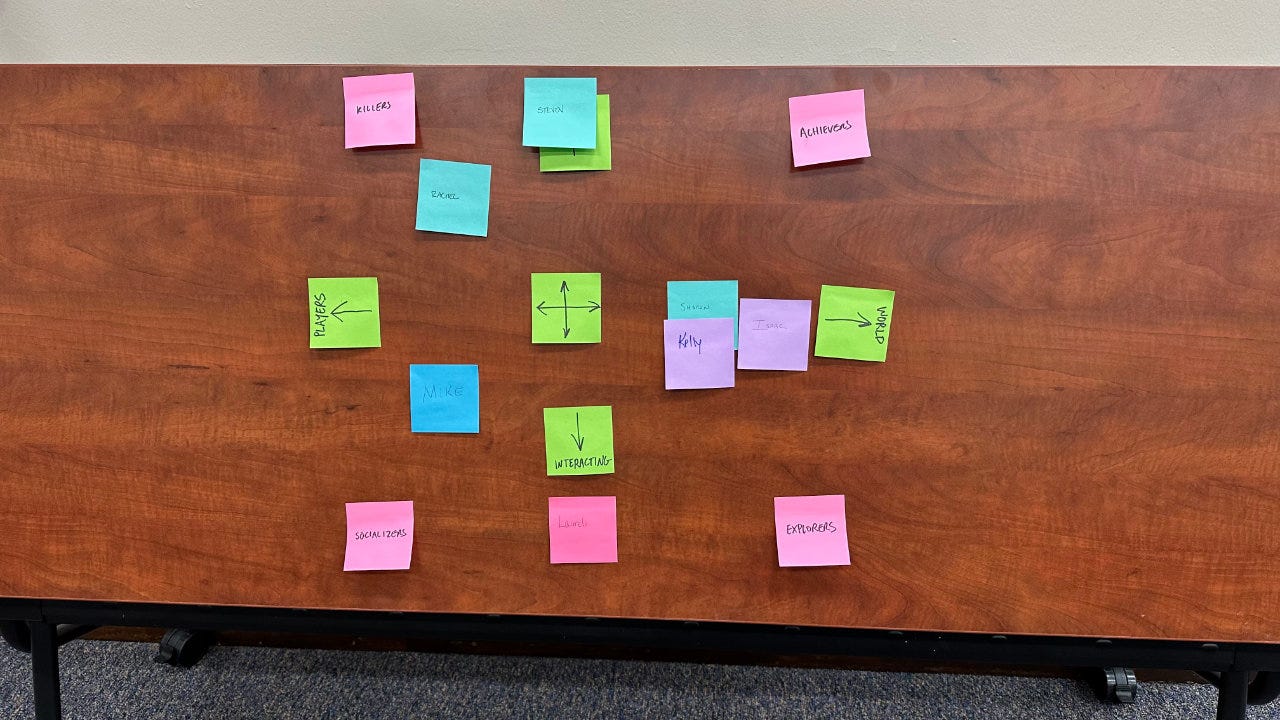

The next exercise was to write their name on a Post-It and put it somewhere on the Bartle Taxonomy quadrants that best matches their own player type.

Normally I’d make some connections to the Quantic Gamer Motivations in this exercise, but we had to shorten it to stay on track.

Principle 2. Choose a theme and zoom in.

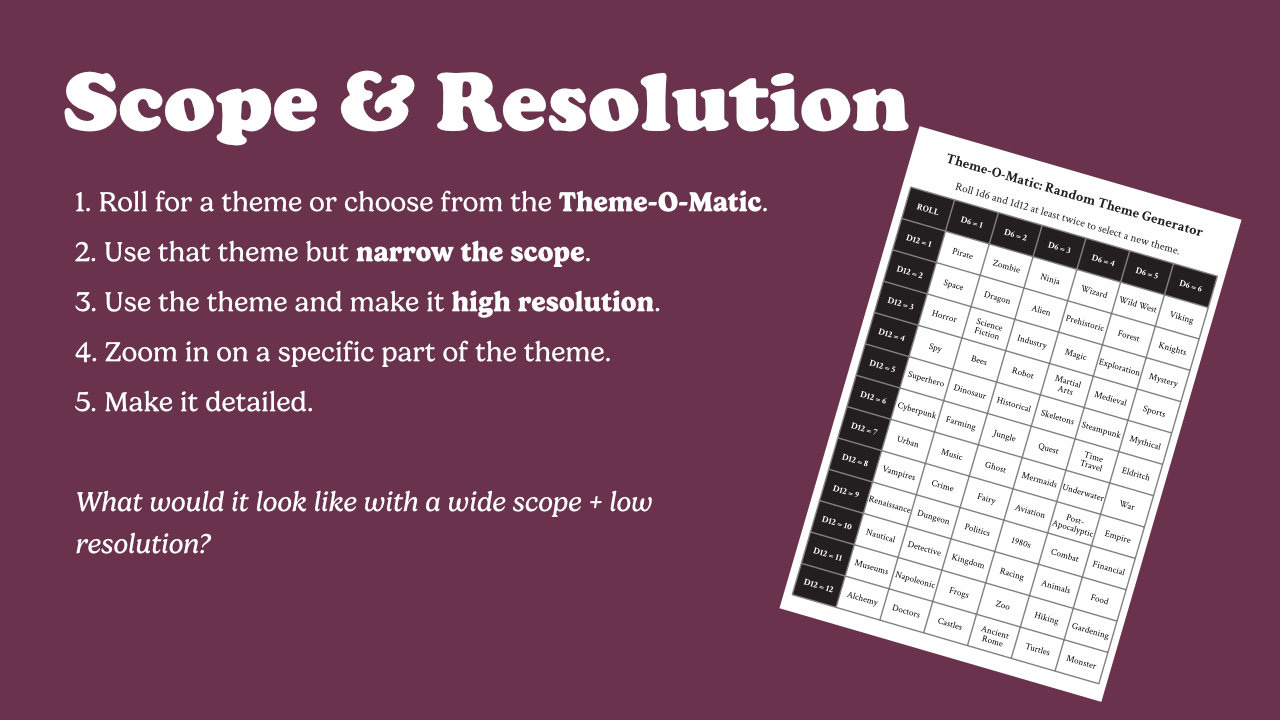

To illustrate Sarah Shipp’s concept of thematic scope and resolution, I spent some time teaching the concept and then we did some easy examples together. I’d offer something like “a game that covers global trade of all materials in the 1700s” and we’d discuss if it was a wide or narrow scope and high or low resolution.

Then we rolled some dice on the Theme-O-Matic and chose some random themes: wizard aliens, Napoleonic aviation, and nautical magic were notable ones for the night.

After picking a theme, everyone tried to narrow its scope and then zoom in.

First, everyone always has a good time rolling for absurd game themes and sharing them with the class. Then we’d work on some of the themes together to see how we could narrow the scope. In every case, just the act of narrowing the scope and zooming in created a more compelling version of the theme. In some cases, it instantly became a great hook.

Principle 3. Design for meaningful choices.

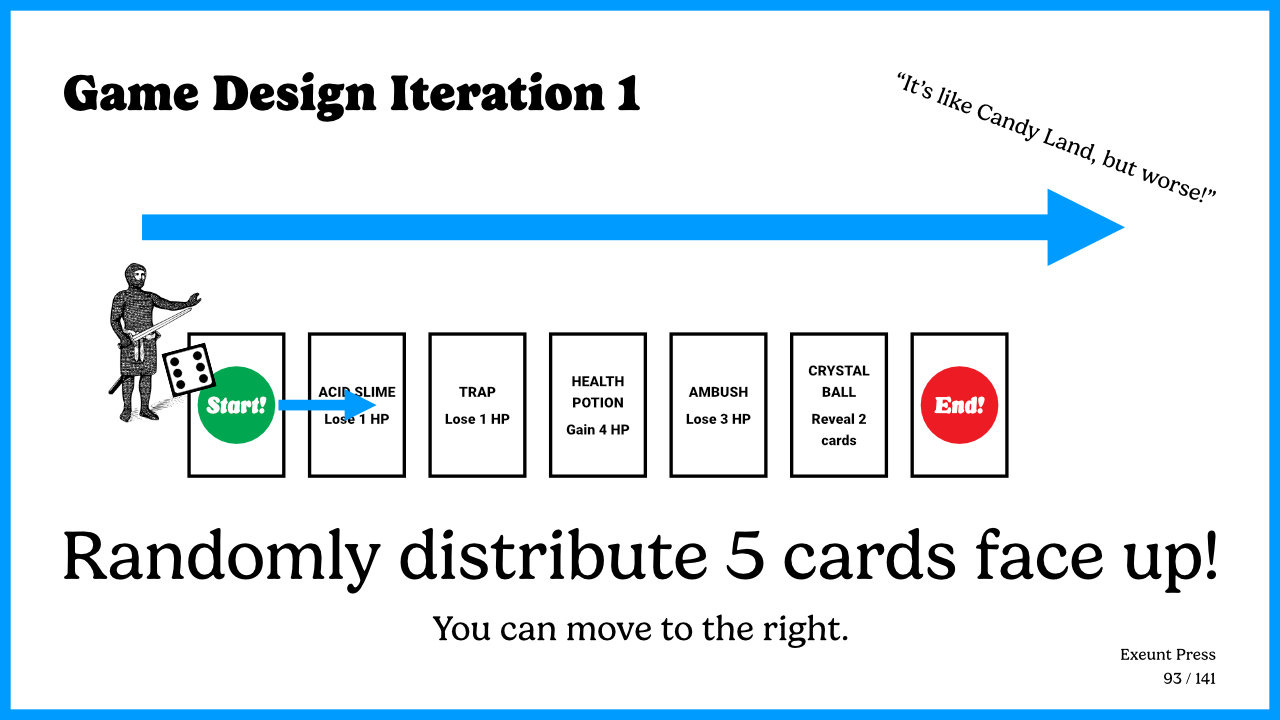

In what I’ve come to call the Worst Dungeon Crawl Ever exercise, we practiced some core concepts of player agency.3

I handed out 10 blank cards, markers, and dice to everyone. We spent some time making custom event cards that caused the player to gain/lose health, move back, or reveal cards. Everyone tried to use the themes they had picked in the previous exericse.

Then we ran through three iterations — the first of which was designed to be as bad and unfun as possible. It has no agency, forcing the player to move to the right each turn

Inevitably, a few players make it to the end, some fail, and others end up in a degenerate game state where they keep looping back to a previous card. We all agree it’s not fun and move on to revised iterations.

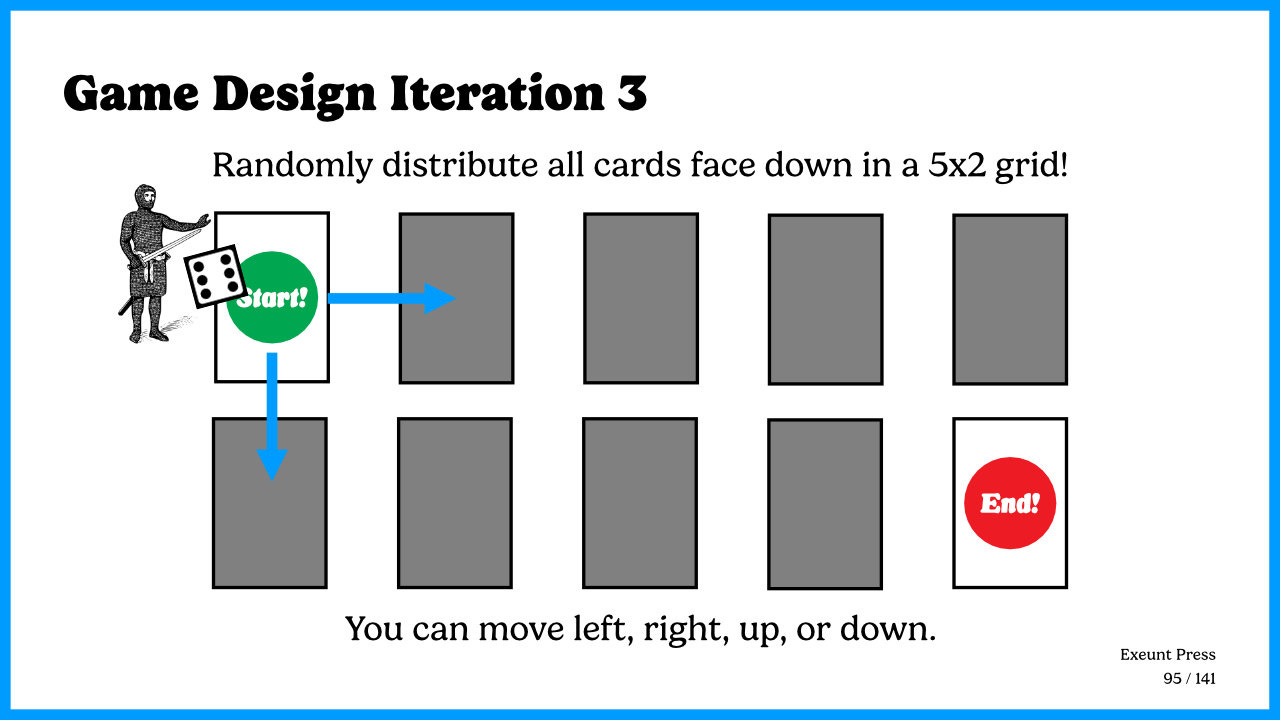

By the third iteration, the cards are now face down in a grid and the player is allowed to choose which direction they’d like to move. It’s still an awful game, but one that we can all agree is better than the first iteration.

The lesson is that applying the CCI model and introducing even the smallest amount of player agency can improve a game design.

Principle 4. Think about your game in three acts.

After a quick discussion of Freytag’s Pyramid and how it shows up in books and movies, we talked about how it also applies to games and interactive media. I’m increasingly convinced that ensuring a game has an arc is just as important as player agency and other design principles.

I tend to agree with Tony Farber of Two Wood for a Wheat on this subject when he argues that not only is a game arc important, it is necessary: “There is no greater insult one can deliver to a board game than to say ‘I felt like I was doing exactly the same thing in the last round as I was doing in the first round’. A board game must move in order to be fun.”

We covered five different ways a game can build an arc and spent some time discussing how we could add a game arc to the card-based dungeon crawls we had made.

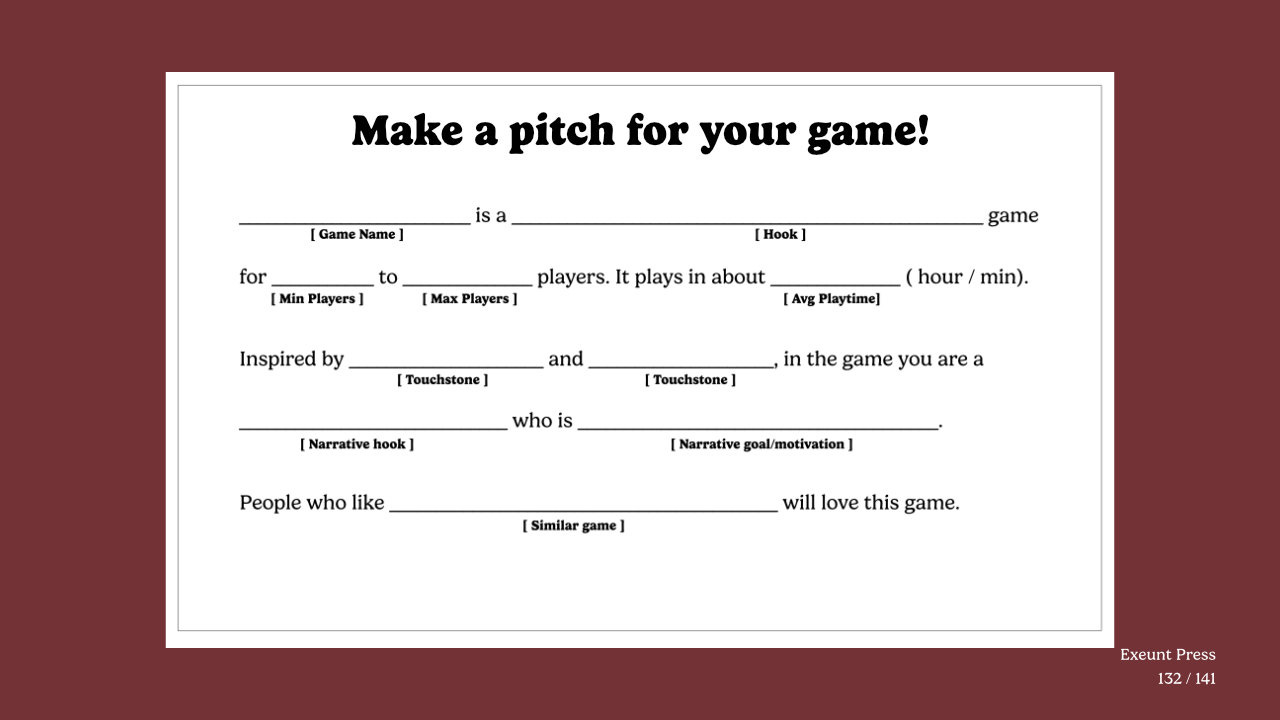

Pitching your game

The final exercise was a Mad Libs style game pitch. I made worksheets that allowed participants to fill in blocks about their games: game name, hook, min/max players, and so on. Of course, in a two-hour class we didn’t have time to fully design a game so we used what we’d like our games to be in the future.

From there, it was easy enough to drop those items into a premade pitch form.

We then took turns reading out some of our pitches. Even though we hadn’t designed full games, it was still fun to hear your theme and ideas converted into a concise and coherent game pitch. There were quite a few pitches that made me really want to play their as-yet-to-be-designed game!

Support your public library

Game design workshop resources

If you are thinking about offering to teach a game design class at your local library, I have some resources that can help:

📘 Make Your Own One-Page RPG from Skeleton Code Machine is available in both print and PDF.4 It covers most topics mentioned above and could be used as a class curriculum. It includes hands-on exercises at the end of each chapter.

📘 ADVENTURE! Make Your Own TTRPG Adventure is available if you’d rather focus on adventure design. Also available in both print and PDF.

Library Game Design Workshops Benefit Everyone is a short list of reasons why game design belongs in public libraries.

Teaching Game Design at a Library has 14 tips for first-time instructors. If you’ve ever thought about supporting your library by offering to teach a class, this is the place to start.

How to Run a Tabletop Game Design Workshop is a one-hour video webinar I gave, hosted by the Indiana State Library. It covers everything you need to know when running a class, including the importance of promoting it ahead of time.

Who are you making this game for? is the first of a four-part series at Exeunt Omnes. Each part gives a detailed breakdown of what I covered when teaching a Make Your Own One-Page RPG class at a public library.

Finally, there are many ways indie designers can support public libraries beyond money. Teaching game design classes is just one way. You can also donate games, collaborate on game nights, promote library events, and more.

Thank you to Gettysburg Library

Thank you so much to both Victoria Freeny and Bob Brown for organizing, hosting, and helping to setup the class at Gettysburg Library. They made sure I had everything I needed and made me feel extremely welcome at the library.

And thank you to everyone who participated in the class! Everyone was so enthusiastic and engaged it made for a wonderful evening. Thank you!

What do you think? Would you consider offering to teach a game design workshop at your local public library? What other questions or concerns would you have before teaching one? What else would you like to know?

- E.P. 💀

P.S. If you love tabletop games, you should check out Tumulus. It’s a print-only, quarterly zine packed with Skeleton Code Machine game design content.

Play some weird and wonderful games at shop.exeunt.press.

Written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. Exeunt Omnes is Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press. For comments, questions, reports from the EZ, or pro tips: games@exeunt.press

Normally I’d have a white board but that wasn’t the case for this class. We improvised by using Post-It notes on a folding tables that were in the room. I think it worked quite well!

This class had more board gamers than TTRPG players, and few were familiar with solo journaling games.

I’m thinking about running a Skeleton Code Machine game jam based on this. If you think that sounds like a fun idea, please let me know in the comments!

Make Your Own One-Page RPG is also available for free in the Skeleton Code Machine article archive.

A jam, you say?

Game Jam! Yes! Let's go!!