A crash course in tabletop game design

I was a guest speaker for two classes at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania. Here are the four design principles that I made sure to cover.

Teaching game design at Dickinson College

I was recently asked to be a guest speaker for two different Dickinson College courses. One course is on the archaeology and history of tabletop games, looking at games like Senet and The Royal Game of Ur. The other is focused on interactive media of all types, but with a focus on activist media. Both classes have the creation of a tabletop game as part of the graded part of the class.

The thing is, many (perhaps most) of the students had no background in game design. Their tabletop gaming experiences were largely limited to the classic games like Candy Land, Monopoly, Clue, and perhaps Catan or Cards Against Humanity.

My task was to teach a single 75-minute session (one per class) that would be a crash course in game design. Give students some core concepts that would help them design games that not only met the course requirements, but might even be fun.

Deciding what to cover (and what to skip) was a challenge, but a problem I really enjoyed thinking about!

Here’s what I did.

With the public library classes I’ve taught, I had four 90-minute sessions. I was able to cover a lot of material, taking participants from blank sheet of paper to published game by the end. That wasn’t going to happen here.

My plan was to instead give students just four design principles — core concepts that they could easily understand and immediately implement in their games.

I wanted to make it clear what they’d get out of listening to me talk for over an hour:

You’ll recognize all of these topics from Skeleton Code Machine posts and Make Your Own One-Page RPG.

Know who your game is for.

The first concept is one that I never used to think about years ago, but have learned how important it is. My first exposure to it in a concise form was Feedback Frenzy at Unpub 2025 in Baltimore. I mentioned it in my SCM article on pitching games, but just as a short paragraph (#8). Knowing “who your game was for” become an important part of a recent library class that I taught.

To me it’s more than simply choosing a quadrant on Bartle’s Taxonomy and picking some of the 8 Kinds of Fun. It’s thinking hard about the core concept of the game and who would want to play it. It’s imagining exactly what that ideal player looks like and why they would love your game.1

Choose a theme and zoom in.

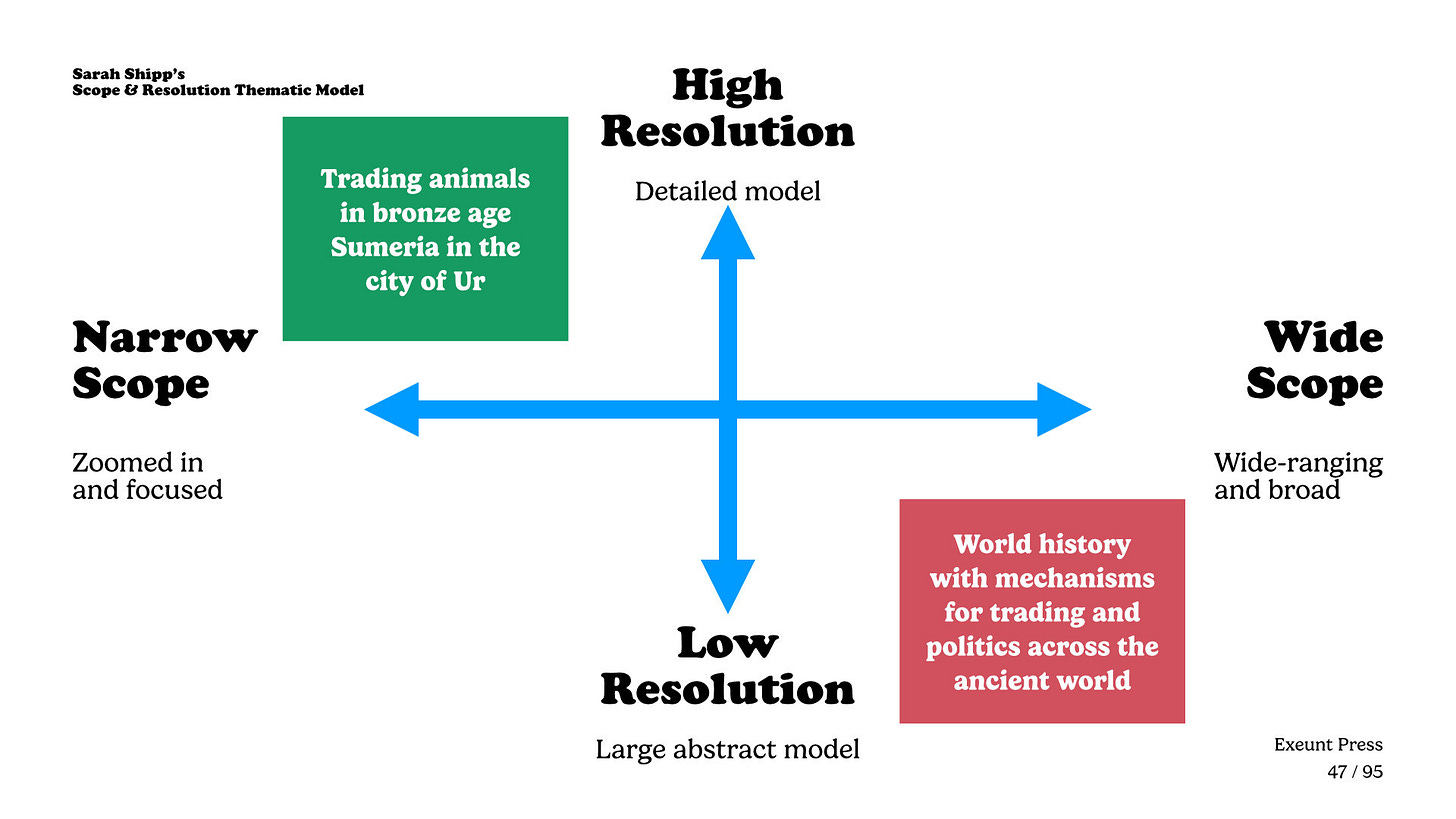

I discovered Sarah Shipp’s Thematic Integration in Board Game Design last year and it has had a profound impact on how I think about games. Her concept of layers of theme is profound and allows us to analyze the thematic design of games.

For the talk, I focused on her distinction of thematic scope vs. resolution.

A game can have a narrow or wide scope. Where a game about the entire world has a wide-ranging and broad scope, another game might zoom in and focus on just one neighborhood. Games can be low resolution, abstracting away detail and not burdening players with highly detailed models. Alternatively, they can be high resolution with an extremely detailed model.2

When selecting a theme for their games, I urged students to start broad but then zoom in. Continue until they had a narrow scope and high resolution. As Sarah Shipp argues, it will result in themes that are more engaging for players, have better marketing hooks, and more intuitive rules.3

Design for meaningful choices.

I’ve written about player agency and if games need agency previously. I continue to be fascinated by the concept of false choices and Hobson’s Choices in tabletop games.

So we covered the basic CCI model of player agency, looked at some examples, and then attempted to make (with a wink) the “worst game of all time.”

Using some simple cards I made ahead of time, we created a simple dungeon crawler. Your character begins at Start on the left and moves to End on the right. We set up and tried three iterations of the design:

All cards begin face up. You can only move to the right.

All cards begin face down. You can only move to the right.

All cards are face down arranged in a grid. You can move any direction.

The first two iterations have zero agency and are awful. The second one is a tiny bit better than the first (maybe) because at least there is some hidden information to reveal. Everyone agreed the third iteration was better because there was at least a simple choice to make — a shred of player agency.

The students said this was the best part of the class, probably because of the hands-on exercise. It seemed to really drive the point home that adding even a tiny bit of player agency can improve a game.

Think about your game in three acts.

The final design principle was to think about how their games can be divided into three acts. This was based on the idea of a game arc, based on Freytag’s Pyramid used to visualize a story arc: setup/exposition, rising/confrontation, falling/resolution.

We briefly covered a few ways to create a game arc including:

Unlocking new abilities

Enabling late-game combos and/or engine building

Stages and boss fights

Expansion and forced conflict

Finally, we talked about the importance of making sure their games actually end in a timely manner. Adding a way to force the game to end was encouraged.

A whirlwind tour of game design

It was a lot to cover in just 75 minutes! The students were attentive and highly engaged, so it went well. I’m not sure there are any critical changes I’d make to the overall structure, but I would consider dropping one of the four topics. Having some more time for discussion and/or activities would have been nice.

My hope is that even if they didn’t retain it all, each student picked up at least one or two tips from the presentation.

I’m extremely curious about what their games will look like!

Thank you so much to Dickinson College for allowing me to spend some time with some of their students. It was a great experience and one I hope to be able to do again at some point in the future.

What do you think? Which of the four design principles that I covered were the most important? If you had to cut one from future classes, which one would you eliminate?

Thanks for subscribing to Exeunt Omnes!

Check out games.exeunt.press for all the latest games and resources!

- E.P. 💀

It’s important to note that this is not necessarily tied to commercial success or even sales. You can make a game just for yourself. You can make a game for your friends or for your classmates. There is no “right” answer here, but it is a question that should be answered with consideration and honesty.

Look up Rule 52.6 “The Italian Pasta Rule” from The Campaign for North Africa: The Desert War 1940-43 (Berg, 1979) as an example of a highly detailed model.

Note that not all games need to high narrow scope and high resolution. Abstract games are extremely popular. Historical wargames are high detailed with broad scope.

I'm a player, not a designer so take this with a grain of salt. For lectures, maybe combining who the game is for along with theme/zoom in. My kids know a game with a naturalist theme is a box I'm going to pick up. The mechanics and play style determine if I'll buy it. Exploring these 2 topics together could be an interesting discussion and help new designers funnel their concept for whom they are actually designing.

Something that always annoys me when talking to someone who makes anything (games, books, visual art, music, anything) is hearing them say their thing's primary audience is everyone. It can be a sale killer for me when I'm at a con/fair.