Epsilon Update No. 3: Plant morphology and classification system

The next monthly update about Epsilon — a solo adventure game about exploring a dark and corrupting forest. Expanding the plant morphology system.

As the launch of Exclusion Zone Botanist: Epsilon approaches, I will be posting regular updates. It’s a chance for you to get a behind-the-scenes look at some of the design decisions and work going into the game.

Follow the Kickstarter pre-launch page to be notified when it goes live!

If you’d like to know what Epsilon is and when it will launch, see the October update.

The world of plant morphology

This month we are looking at the Epsilon plant discovery system and how it uses plant classification systems and morphology.

Plant morphology (i.e. phytomorphology) is the study of the physical form of plants.

It’s a way to classify and describe the external structures of a plant, as opposed to plant anatomy which studies (mostly) the internal structures of plants. Morphology focuses at the macro level with the things you can readily see when looking at a plant. Anatomy (again, mostly) focuses on the internal and microscopic parts you can’t see just by looking at a plant in the wild.

In the original Exclusion Zone Botanist, this morphology was determined in three steps using six-sided dice:

Plant size: Roll 1d6 to determine if the plant is relatively small, medium, or large in overall size.

Leaf shape: Roll 2d6 to determine the general leaf shape based on 11 different classifications (e.g. ovate, lanceolate, etc.) selected from the many actual types.

Leaf arrangement: Roll 1d6 to select one of three arrangements for the leaves such as alternate or opposite.

When combined with the “unusual features” (e.g. “Thick mucous coats the trunk, branches, and all the leaves.”), this provides enough narrative prompt for the player to be able to sketch the plant. It’s just a few dice rolls and it works rather well.

And yet I’ve had people who love Exclusion Zone Botanist tell me that they wished there were more variety in the plant prompts. Not necessarily in the unusual feature lists, but specifically in the other lists — the plant morphology prompts:

“The first time I played EZB I just wanted to roll bigger charts — leaf types were represented but I wanted more kinds of flowers in more kinds of bloom configurations (single, compound, racemes, etc.), different fruits and berries, with different seeds. As someone who loves plant taxonomy I was just thinking of soooo many combinations that were not represented, and then I wanted to doodle them in my field journal. *tips botany nerd hat*” — Wonder & Whimsy

I’d love to add more plant morphology into the game! There is a massive glossary of plant morphology just waiting to be incorporated. But I also want to be mindful that not everyone wants a ton of dice rolls for every plant. It can be a trade-off between prompts and dice.

The Cronquist classification system

One way that Exclusion Zone Botanist: Epsilon will handle this challenge is by adding a higher level classification, rather than many granular morphology details. Think of it as a broad archetype given to the newly discovered plant, and then specific details can be filled in from there.

To do this, I’m using the Cronquist system of classification for flowering plants.1

Just like libraries have classification systems for books (e.g. the Dewey Decimal System), botanists have systems for cataloging plants.2 And just like there are multiple classification systems for library books (some of which have fallen out of favor over time), there are multiple systems for plants.

The Cronquist system, originally developed in 1968, divides all flowering plants into two broad classes of dicots and monocots, and then into subclasses, orders, families, and so on. By 1981 the system had been revised to include 83 orders and 386 families of plants.

What I noticed about this system was that the dicots class (Magnoliopsida) had six distinct subclasses. These subclasses mapped easily onto the roll of a six-sided die: Magnoliidae, Hammamelidae, Caryophyllidae, Dilleniidae, Rosidae, and Asteridae.

The subclasses were based on the plants having similar structures and outward appearances — perfect for narrative prompts!

The monocot class (Liliopsida) was a little trickier because there are only five subclasses. This was easily solved, however, by splitting the Liliidae subclass into its two orders of Liliales (e.g. lily, iris, aloe) and Orchidales (orchids). With six classifications, it easily maps onto the roll of a die just like the dicots.

Epsilon plant discovery mechanisms

When a new plant is discovered in Epsilon, the player will first roll dice to determine the Cronquist class (monocot or dicot) and subclass.3 Each subclass is presented with the subclass name, key words, description of defining features, and a few real-world examples with both common name and scientific name.

This classification serves as a quick archetype or blueprint for what the player found. It packs a lot of information into a die roll, but at the same time allows the player to pick and choose what they want to use from it.

For example, the Caryophyllidae subclass includes plants that contain betalains (derived from the Latin word for the common beet) for pigmentation rather than anthocyanins. This gives the plants unusual and often vivid red, violet, yellow, and orange colors (e.g. Swiss chard). Along with the rest of the description, the player might choose to incorporate this coloration into their finding.

After the classification, the player will still roll for size, leaf shape, and leaf arrangement. This will be done, however, with the classification in mind — not so much as “rules to apply” but a framework or scaffold that is there if they need it.

Also the leaf shape and arrangement types are being significantly expanded, as that’s easy to do without adding more dice rolls. The 2d6 simply becomes a D66 random table. The leaf shape table, for example, will be expanded to at least 18 types.

Extra morphology random tables

When creating Tollund, I added some extra random tables to the back of the book. They are never specifically required while playing the game, but are there if players need them. My thought was that if you get stuck and need some help, the tables might get you unstuck. There are tables for small items, signs and omens, nearby locations, and members of the village. Players have seemed to really appreciate having them.

I’d like to do the same with Epsilon, including even more plant morphology tables that are fully optional and not required by the rules. Some examples of ones that will probably be included are: fruit/seed traits, specialized structures, flower characteristics, and pigmentation. So if you want to really dig deep into botany, it’s all there for you. But it’s also OK to skip it!

But what about APG IV?

The Cronquist system was developed based on literature, botanist advice, and inspection of specimens. As such, it was very focused on the physical form of the plants. That makes it perfect for inclusion in a game that’s all about visually inspecting plants and trying to draw their external appearance.

But it’s also probably not the best classification system when it comes to real-world science and botany.

By the 1990s, it was possible to do widespread genetic testing of plants in a field called phylogenetics. This meant that rather than classifying plants based on what various specimens look like (or perhaps some chemical analysis), they could be classified into groups that include all the descendants of a common ancestor (i.e. a monophyletic group). Once the actual genes of plants could be sequenced and analyzed, it became clear that it didn’t match some of the visual classifications. The Cronquist system fell out of favor and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG) system has become arguably the most authoritative system in use today.4

So why not use the APG system in Epsilon?

Well, in part because it is a more complex system. I don’t want the game to read like a botany text book and am very careful to keep the science stuff light. In addition, because it’s based on genetics and not visible morphology, it doesn’t really meet the goals of why I’d want to include it. I want a simple classification system that groups similar looking plants together. The Cronquist system does that quite well!

Follow the Epsilon project

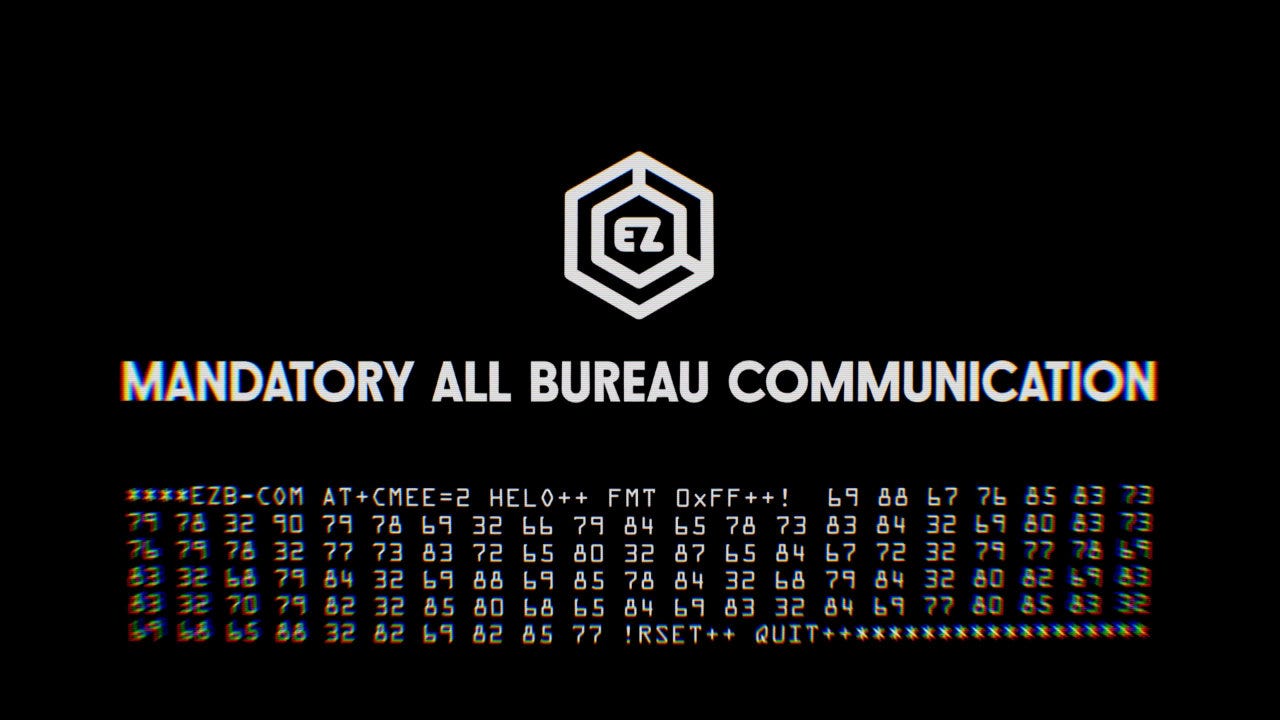

In future updates, I’ll talk about both encounters and the EZ map, which might be a pointcrawl… because everything is pointcrawl.

🌿 If you haven’t already, join 800+ others and follow the pre-launch page on Kickstarter.

- E.P. 💀

P.S. If you love tabletop games, you should check out Tumulus. It’s a print-only, quarterly zine packed with Skeleton Code Machine game design content.

Play some weird and wonderful games at shop.exeunt.press.

Written, augmented, purged, and published by Exeunt Press. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form without permission. Exeunt Omnes is Copyright 2025 Exeunt Press. For comments, questions, reports from the EZ, or pro tips: games@exeunt.press

It was developed by Arthur Cronquist (1919 - 1992), an American biologist, botanist, and Linnean Medal recipient.

If you’ve never read about the background and impacts of the Dewey Decimal Classification, you really should.

In the Exclusion Zone, dicots are going to be more common than monocots. Therefore results will be weighted toward finding dicots. Right now it is set at 1d6: 1-4 = Dicot, 5-6 = Monocot. That is, like everything in these updates, subject to change.

The APG system has been revised multiple times since APG I in 1998. The latest APG IV system was published in 2016.

💙 random tables.

Also, yeah, boo to Dewey.